Kamala Harris delivers first speech as vice president-elect

Famed journalist Arshad Waheed passes away due to Corona virus

Don’t ban, train the media

—By Lubna Jerar Naqvi

She is a member of the Executive Committee of the Karachi Union of Journalists (Pakistan).

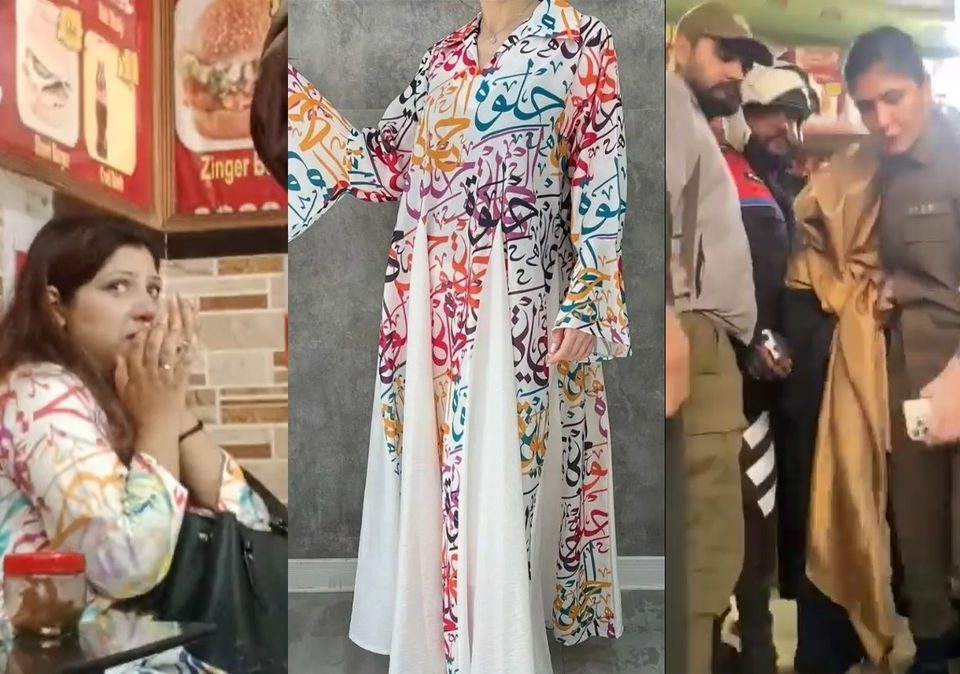

The news first became viral on social media and then broke TV news channels in the first week of September 2020.

And soon the details of the Lahore (later Lahore-Sialkot) Motorway gang rape incident were being discussed everywhere.

There was immense outrage at the incident as it was no doubt a shocking incident involving a young mother and her children. It resonated with a large section of society and the anger spread to all sections of society.

The media was inflamed and we saw an unprecedented emotion from many journalists especially men, who were quite vocal against the authorities and the lack of safety on the roads of Pakistan.

There were demands for justice for the survivor and her children, as well as a popular demand on social media as well as other media for public hanging for the criminals. These demands and the growing anger was adding to the pressure on the authorities that seemed to flustered by pushback from the otherwise indifferent society.

The frustration of the authorities increased when the CCPO Lahore blamed the survivor for travelling alone at night, only to evoke a backlash from the angry public, putting the provincial and federal governments into the spotlight.

And it didn’t help that the media was closely following the story, holding the government responsible and keeping them on their toes. The media pressure probably helped to expedite raids and arrests.

However, despite the pressure the main culprit managed to escape the police, which lead to loud criticism of the authorities and raised questions about their competence.

Days passed and the media kept keeping an eye on everything related to this case – and with no arrest of the main culprit, tensions were mounting.

And then suddenly there was silence as the media was banned from reporting on the case.

The investigating officer had filed an application in court for a ban under Section 13(2) of the Punjab Witness Protection Act 2018.

The law states, “The reporting of the identity of a person connected with an offense of terrorism or a sexual offense, or the identity of the members of his family, shall be prohibited in print, electronic or other media, if the court is satisfied that the quality or voluntariness of the evidence of the person concerned will diminish thereby.”

And an anti-terrorism court (ATC) in Lahore ordered the media ban, as it was observed that the crime was an offense of sexual nature and the media coverage of the case would cause disgrace to the survivor and family.

Following the court order, the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulation Authority (PEMRA) issued a notification on October 2 in which it ordered all TV channels to follow the ATC Lahore’s order and refrain from airing any content about the case.

Senior journalist Afia Salam said that,

“PEMRA has a habit of being very silent and almost blind to many of the things that do fall under its mandate that it should be taking notice of regarding the kind of content that is put out including hate speech. The ban on covering this particular incident I think was an overreach of authority.”

This was unfortunate, since crimes against women and children are already under reported in Pakistan. The pressure generated by the media based on public sentiment usually helps to keep such cases in the spotlight and get speedy justice like we saw in the Zainab Ansari of Kasur’s case.

Therefore, it was important that PEMRA – or anyone else – didn’t cause any hiccups for the media be allowed to keep doing its work in an important case like the Motorway incident. And if there were complaints, these showed be shared and then action taken.

“There is a clear process given for PEMRA to take action, so we need to know whether its Council of Complaint received complaints regarding the coverage of the incident.” Said Salam. “What was the discussion that took place; what was the consensus; how many people in the Council agreed to issue the kind of notification that they did regarding ban on discussion; how many opposed it on the point for infringing on freedom of expression from journalists.”

Such bans on the can be extremely dangerous and detrimental for media freedom in a country where freedom of media and expression has always been a delicate thing.

“This is not a court case that was being reported on.” Salam added. “We do not have those kind of juries which can be influenced by the reports, so I think it was totally uncalled for and it sets a very bad precedent on the manner in which journalists are supposed to do their duty and ask questions and speak truth to power. So I really don’t think that PEMRA’s action can be justified from any angle.”

Commenting on the role of the media, Absar Alam – journalist and former chairman of PEMRA – said, “I don’t think media crossed any line covering this particular incident and has instead displayed professional responsibility.”

Alam added, “The ban was not directly by PEMRA but PEMRA used a court order to slap this ban. Legal experts claim that PEMRA doesn’t fall under that particular court’s jurisdiction, so PEMRA should have shown some caution and sought a second opinion before rushing for this ban.”

“There exists a possibility of this precedent being used to restrict media coverage of other issues, unfortunately. Not only PEMRA but Pakistan Broadcasters Association should also take responsibility to challenge such bans in high courts.” He said.

Afia Salam said while commenting on the media ban and its repercussions on the future of journalism, “If this goes on then it would put a clamp down on all kinds of questions that are being asked in the manner any investigation is taking place or in the manner of which is a journalistic duty to ask questions about how a case is proceeded against.”

Tasneem Ahmar, director of the Uks Research Centre and executive producer of Uks Radio, added, “We need to face the challenges instead of banning things. I agree that the media did not reveal the name of the motorway gang rape case survivor- which I think is commendable. Unfortunately, the cases of all child rape and others that have followed have all violated the ethical guidelines. The names of the child becomes the identity of the case, the parents and other relatives are interviewed thus revealing their identities. Yes, in many cases the child is no more with us, but the sanctity of the family is compromised.”

She said that the Section 13(2) of the Punjab Witness Protection Act 2018does‘not say that these are only applicable to victims and not the survivor. So, somewhere the class and background of the victim or survivor has an edge over those whose bodies are found at a trashcan’.

On the other hand,Kamal Siddiqi, journalist and director of CEJ said “PEMRA followed up on a court order. I think the rationale was not to prejudice the proceedings.”

Crimes against women and children are under reported, and these have only been highlighted in Pakistani media after Zainab Ansari’s case in 2018.The media is learning how to report on such sensitive newsand probably need some guidance in this.

Ahmar said, “To keep an issue alive, the media and through them, in the minds of the public, the media need to focus more on issues that are directly related to the case, but will not hinder the investigations. By giving ball-to-ball commentary on the efforts of the police etc. does help in cautioning the perpetrator.”

Adding, “Media are important sources of public ideas about VAW and VAC. However, if we analyse the media coverage of Motorway Rape case, it is evident that though the media did raise very important questions, specially the statement by CCPO Lahore, many a debates and discussions were given a very politicized angle. That wasn’t helpful at all.”

She does not agree with the ban.

“Imposing a ban on the media to cover particular news is the easiest. But that does neither address the issue nor understand it. If the PEMRA felt the media was indulging in ‘reckless coverage’ of the case, and I agree that some of the media did cross the lines, the solution is not in banning all media. The better and much required solution is to train the media on how to cover sensitive stories- rape and all forms of sexual offences – being on top.”

She said that banning this story can not only be an attempt at silencing the media on important issues like rape but also set a precedent to ban media coverage for other important stories.

Ahmar thinks there is a need for proper training of the media as well. “As for training the media on sensitive and sensitized reporting on Violence against women (VAW) and violence against children (VAC), Uks has already shared with the media a Gender sensitive code of Ethics, as well as a report on, ‘How the Pakistani Media Reports on Rape. These are good resources for the media if they would like to adopt them. What actually happens is that the media –most of the- compromises on ethical guidelines in the rat race to top the Breaking News syndrome.”

However, Ahmar does stress the need to keep the conversation about violence against women and children going and what better way to do this is through the media.

“Though we cannot compare the motorway gang rape case with the Delhi/Narbhaya Rape Case of December 2012 by many seen this as the turning point for media, public discourse, have acknowledged the later as there was a heightened awareness of sexual violence against women.”

“We can, try and keep the discussion alive through discussions on issues of sexual violence against women, girls and boys. The focus should be on trauma, stigma, legal battles that the victim/survivor have to go through, the media trail that is said to be the ‘second’ rape and most importantly the lack of empathy when reporting not just rape, but even harassment (on- and off-line), molestation, safety on roads- in short – making our country liveable for women and children.” She said.